|

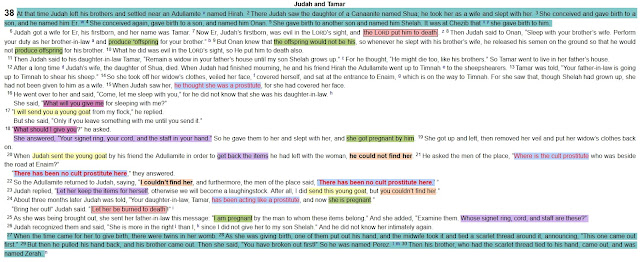

| "There has been no cult prostitute here." (HCSB via Logos) |

Don't

forget the scandal.

Grace in the midst of vile

This is

one of those chapters in which parents of the West are tempted to say at the

end of chapter 37, "OK, kids; off to bed. We'll read chapter 39 tomorrow

night." Genesis 38 functions as shock factor. The entire chapter. Sordid.

Divine execution. A defiant sex act. Betrayal. Seduction. Prostitution.

Hypocrisy.

The sleaze

factor in Genesis 38 does not provide the real scandal. The real scandal is how

Moses wants us to see grace at work in the midst of the vile. In Genesis 38,

there is an avalanche of grace flowing out of the debauchery. Brilliant faith.

Justification. Redemption.

Oh yes. In the midst of Judah's self-inflicted cesspool, grace cascades. The one great storyline of redemption through the Seed isn't simply unorthodox. It's unwanted. It undermines, no, it smashes a self-righteousness we've convinced ourselves is righteous.

Oh yes. In the midst of Judah's self-inflicted cesspool, grace cascades. The one great storyline of redemption through the Seed isn't simply unorthodox. It's unwanted. It undermines, no, it smashes a self-righteousness we've convinced ourselves is righteous.

The seed

It is true

that Moses is not writing about the morality

of seducing someone who Is not your husband. It's also true that Moses is highlighting the divine preservation of the Genesis 3:15 promised "Seed of the

woman" in the storyline, especially the storyline as it unfolds through

Judah in the book of Genesis. The birth of Perez belongs to the OT stories of

"miracle" births of sons in the pedigree of the coming Messiah. It is

unexpected. It occurs in the midst of extenuating and extraordinary

circumstances. The story of Genesis 38 most certainly is about "the seed,

the heir, the firstborn." In this story, Moses is interested in making

sure his readers are not in the dark regarding the origins of the

still-yet-to-be-realized royal bloodline traced through Judah and his son,

Perez.

But it's not simply about the seed. 1 Corinthians

10 tells us that these OT stories were meant to be examples for us. However,

the "examples" for us are not morality plays, but part of the great

unfolding story of redemption in the Old Testament. The "examples",

as Hebrews 11 demonstrates, are aimed at eliciting saving faith in the

community, faith that wraps its hopes around the promise of a Messiah.

Tamar is

certainly best understood against the backdrop of Genesis 3:15. All of the Old

Testament progresses the Genesis 3:15 storyline to its culmination in the

Person and work of Jesus. There are grace and faith elements in this story that

Moses draws attention to for the sake of his audience.

A couple of hermeneutical considerations

A couple of hermeneutical considerations

There are

a couple of hermeneutical considerations underlying the story of Tamar and

Judah that spotlight grace and salvific faith. One is an idea Paul picks up on

in Romans 11. The role of Gentiles in redemptive history is meant to provoke

Israel to repentance and faith. This is fundamental to understanding the story

of Jonah. It's certainly at the heart of the story of Namaan. The book of Ruth

also has "Gentile provocation" as an undercurrent. Throughout

redemptive history, God has used Gentiles who embrace the true God of Israel as

their own as provocative motivation for Israel to repent and confess their

fidelity to the one true God. When we find a Gentile or "pagan"

confessing allegiance to Israel's God or expressing the kind of faith expressed

by Abraham (see Genesis 15:6), we can be sure that the story has been included

in sacred revelation to not only show that "salvation has come to the

Gentiles" (i.e. foreshadowing the great inclusion of Gentiles as True

Israel in the New Covenant), but also "to make Israel jealous."

(Romans 11:11)

The other

consideration is what I call "the Pharisee factor." Israel in the Old

Testament. Pharisees in the New. Both Israel and the Pharisees suffered from

acute self-righteousness. Much of recorded revelation is aimed at ridding

Israel (and us) of its natural inclination to promote self. We most clearly see

such heart attitude on display when scandal is present in the text. A comment

recorded by Luke could function as a thesis statement which underlies Israel's

self-righteousness. When a woman of ill repute washes Jesus' feet with her tears

and anoints them with fragrance, the Pharisee who invited Christ to the dinner

expresses centuries of Israel's self-righteousness toward the scandalous:

"This man, if He were a prophet, would know who and what kind of woman

this is who is touching Him—she’s a sinner!” (Luke 7:39). Israel's

preoccupation with self-importance as the "apple of God's eye" led

them to look down on the scandalous. This is a running theme in Jonah, can be

found in Job, and litters the indictments of the prophets, especially Amos and

Hosea. The inclusion of Gentiles in the redemption storyline is aimed at

knocking Israel's inflated ego down a few pegs.

Five scandalous elements in the Tamar story

The above considerations relate to the story of Tamar in the following five ways:

Tamar is a Gentile. This can easily be missed.

It's not mentioned in the text, but the entire backdrop of this story occurs

among the Canaanites, or more specifically, the Adullamites. It's also easy to

overlook Tamar because initially, she is introduced into the story as simply a

supporting character.

Tamar is a woman. This can also easily be

missed, especially in a day in which women in the West enjoy the kind of life

that would be quite foreign to the women of the ancient near east. Early in

this story, Tamar "is given" to Judah's son to be his wife. As the

story reaches its climax and resolution, we find Tamar in the proverbial

driver's seat. For a woman to take this kind of initiative in that culture was

quite risky, especially when facing the charges Tamar was facing (the death

penalty). A woman who takes initiative in a public way belongs in the same

societal "class" as prostitutes.

Tamar seduced Judah. Her actions are described

in the text, by her own kind (or by her own mouth, we are not told) as that of

a prostitute. The activity by which she secures the royal line of Judah is

deception, which seems even more spectacular than that of Jacob stealing Esau's

birthright. Even Judah's initial judgment of capital punishment is that which

is reserved for those who engage in sexual promiscuity (Leviticus 21:9).

Tamar is commended. Judah's declaration of

"not guilty" isn't simply an acknowledgment that Tamar is a better

person. Judah's statement carries implications beyond its initial event.

"She is more righteous than I" recalls Genesis 15:6: it was counted

to her for righteousness. Judah's statement also doubles as his own indictment.

If Tamar is not guilty, then it is Judah who is guilty of a lifetime of

covenant faithlessness, manifested in the way he has put Abraham's posterity in

jeopardy. Her commendation is later picked up by the women of Bethlehem in the

book of Ruth, pronouncing blessing on Naomi (and Ruth) after the same kind of

generational blessings enjoyed by Tamar (Ruth 4:12).

Tamar acted in faith. As the scope of the

narrative widens out after the initial deception and legal pronouncement of

innocence by Judah, and we begin to see the place of Genesis 38 in the wider

plotline being traced by Moses, Tamar plays the role of the one being aligned

with the "Seed of the Woman" in the unfolding plan of redemption (see

Genesis 3:15). She is more righteous than Judah. She, not he, has been acting

in faith. Childless, she exercises her faith and ends up in the Royal line of

David that eventually produces the Messiah.

Gentile + woman + prostitute + commendation + faith =

scandal.

An Old

Testament "Pharisee" would have blanched at such a thought. Commended

as *more* "righteous"? Shameful.

A Gentile who not only prostitutes herself in seducing one of Israel's Big 12,

but is "let off the hook"? Preposterous.

Commendation in place of the expected condemnation? Offensive. Perez as a blessed child of The Promise? Disgraceful. The coming Savior of Israel rides

on the actions of a Gentile prostitute? Absolutely

scandalous. What a despicable affront to any who might begin to believe

in Israel's "exceptionalism" as exhaustively exclusive. “This Moses,

if he were a prophet, would know who and what kind of woman this is who is

being commended as righteous—she’s a sinner!”

But that's

precisely the point: a sinner declared righteous. Three times the result of the

search for Tamar is described as they "didn't find her". Twice in the

middle of this story the statement is made, "there is no cult prostitute

here." At the end of the story, Tamar is commended as being

"righteous".

"There

has been no cult prostitute here." Situated at the center of the story (see highlighted text above), that statement screams across the pages of

this sordid tale too good to not be true. "There has been no cult prostitute

here." They couldn't find her; they didn't find her; they'll never find

her. Ever.

When Tamar

plays her card as the "item keeper" bearing the finery of her "king", the

true prostitute is exposed as the one pointing the finger. The indictment is

devastating. Judah is no better than his sons. God executes judgment (Genesis

38:7,10) . Judah orders judgment in the same fashion. (Genesis 38:24b -- again, see the highlighted graphic above).

But there

is no cult prostitute here. The story has moved from barren widow (Tamar) to

one declared righteous (Tamar) to a blessed child of promise (Perez). Rather

than being an object to be tossed on worthless heap, Tamar is a recipient of

divine favor exposing the Hebrew charlatan for who he is. Carrying a child who

perpetuates the Promise, the sinner is declared righteous.

A sinner

who is declared righteous. How scandalous is that?

One other

scandalous feature of this chapter should be considered:

Tamar saves Judah. If it's not scandalous

enough for a "seduction" to be commended as "righteous",

try "Gentile becomes catalyst for Hebrew's redemption" on for size.

In this regard, the figure of Tamar in Judah's story is of the same cloth as

Rahab and Ruth. Like them, her faith expressed in speech and action is used to

bring about the redemption of Israelites, in this case, Judah. Exposed by

Tamar's righteous deed, from this point on, a chastised and repentant Judah

begins to live out his destiny as one through whom Israel's future king and

redeemer would come.

Grace

doesn't always show up cloaked in the pretty. We would do well to avoid the

morality play that acknowledges grace in this story, but does so along the

lines of God making lemonade out of lemons (i.e. Because I'm the great God I

am, I'm going to grace the story with Perez in spite of all the filthy sinners

here). It's true that God does providentially work grace in the midst of the

mess, but he does so in a way that is not arbitrary, but shocking.

Gospel Question #1: One

legitimate question arises from Moses portrayal of grace against the backdrop

of scandal: how far are we willing to go for the sake of the gospel? Tamar

could have been killed for what she pulled off. A woman? Seduction? She put it

all on the line on the road to Timnah because something bigger than herself was

at stake. Like others listed in Hebrews 11, Tamar is an example to us of faith

that doesn't walk by sight.

Gospel Question #2: But we

also must ask ourselves: how far are we willing to go to see ourselves as the

recipients of cascading grace in the midst of our mess? Within the sordid tale of Tamar and Judah, we find the gospel brilliantly shining. The gospel tells us that we have all played the Judah. We've lived the lie. We've played the fool. We point the finger to distract from our own prostitution. In Tamar, the gospel confronts us with our own hypocrisy.

Embrace the scandal of the gospel. We embrace the scandal of Genesis 38 as part of the unfolding of the grand story of Jesus because Matthew does so in Matthew 1. Tamar (along with Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba, and Mary) is specifically mentioned in the pedigree of Jesus because in Matthew 1, Christ's own scandal is unfolding in the story of his birth. The disgrace of (supposed) illegitimacy dogged Jesus all the way to the cross. Thus, in Christ's life and death, scandal becomes part of our identity in Christ.

Embrace the scandal of the gospel. We embrace the scandal of Genesis 38 as part of the unfolding of the grand story of Jesus because Matthew does so in Matthew 1. Tamar (along with Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba, and Mary) is specifically mentioned in the pedigree of Jesus because in Matthew 1, Christ's own scandal is unfolding in the story of his birth. The disgrace of (supposed) illegitimacy dogged Jesus all the way to the cross. Thus, in Christ's life and death, scandal becomes part of our identity in Christ.

In Christ,

"there is no cult prostitute here". We know we're guilty. Prostitutes

all are we. But Christ died bearing our guilt. And we're declared righteous.

Scandalous.

3 comments :

Ah....there is beauty in the scandal.

Many great statements....two that stand out in the same paragraph.

"Grace doesn't always show up cloaked in the pretty."... "It's true that God does providentially work grace in the midst of the mess, but he does so in a way that is not arbitrary, but shocking."

Why the shock factor? Why does God, all throughout the Bible shock us? Does this black canvas of a fallen world make grace look all the more resplendent? Do we see Gods varied grace on display in multi-faceted color.

Do Gods shock and awe tactics help Gods people understand the depths to which the Son has descended into the mire of this world, in order to save a people living in the valley of the shadow? I would think so. The story of Tamar makes God look brilliant; the Great indestructible Line of the Seed is protected; He is moving the storyline forward...until we arrive at the greatest scandal in human history...the sinless Son on an obscene cross bearing the weight of my full and deserved wrath...

Great insight, Chad! I just saw this, and it sparked some thoughts that I've recorded over at my blog- https://danwstanley.com/2016/04/16/a-tale-of-two-brothers/

Thanks for the reminder about this post. I have passed it along to others, and recommend that it be included in your upcoming volume, "The Collected Sermons of Chad Bresson" along with the one on Stephen in Acts 7 delivered at the John Bunyan Conference.

Post a Comment